Everyone who lives near the lake knows the stories about the world underneath it, an ethereal landscape rumored to be half-air, half-water. But Bastián Silvano and Lore Garcia are the only ones who’ve been there.

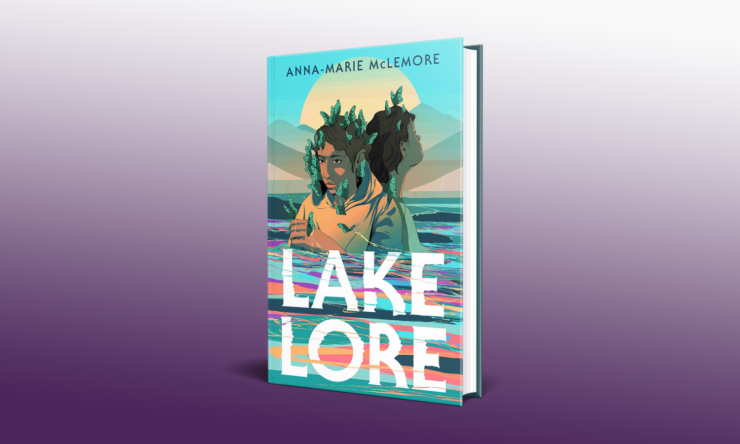

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Lakelore by Anna-Marie McLemore, out from Feiwel & Friends on March 8th.

Everyone who lives near the lake knows the stories about the world underneath it, an ethereal landscape rumored to be half-air, half-water. But Bastián Silvano and Lore Garcia are the only ones who’ve been there. Bastián grew up both above the lake and in the otherworldly space beneath it. Lore’s only seen the world under the lake once, but that one encounter changed their life and their fate.

Then the lines between air and water begin to blur. The world under the lake drifts above the surface. If Bastián and Lore don’t want it bringing their secrets to the surface with it, they have to stop it, and to do that, they have to work together. There’s just one problem: Bastián and Lore haven’t spoken in seven years, and working together means trusting each other with the very things they’re trying to hide.

BASTIÁN

The first time I saw Lore was near the inlet. At first, I thought the motion rippling the brush was a mule deer, but then I saw someone running. Not running in the laughing way you would with friends—they were alone—or even how you run to get somewhere. They were running in the frantic way of trying to get away from someone, stumbling out of the brush and onto the rocky ground, checking back over their shoulder every few seconds.

I guessed they were about my age. And maybe this is because I’m trans, and always looking out for it, but I got the flicker of recognition that comes with finding someone else like you. A feeling that whatever words this person got assigned at birth maybe didn’t fit them either.

Buy the Book

Lakelore

It wasn’t really any one thing about them. The dark brown of their hair was in two braids, heavy enough that I could hear them hitting their shoulders as they ran. Their jeans had a rip in the knee that looked recent, not yet frayed. Blood and gravel dusted the edges of the rip, like they’d just fallen.

Their T-shirt was the orange yellow of Mamá’s favorite cempaxochitl, the kind of marigold that looks like firewood crumbling into embers. Which wasn’t doing this person any favors if they didn’t want to be spotted.

None of that told me anything for sure. Gender identity never reduces down that easily anyway. Recognizing someone like you is never as simple as picking things apart to see what they add up to.

They tripped, hard, hands hitting the ground in a way that made me wince.

I went halfway up the path from the inlet, close enough to yell, “You okay?”

They startled so hard that I knew I was right. They were running from someone.

“Do you need help?” I asked.

They looked around for where my voice came from, and found me.

Maybe it was seeing someone else like me, brown and maybe trans, that made me call out, “Come on.”

I planned to help them hide out behind the rocks. Then I saw the first flicker of iridescent blue lift off the water. It fluttered through the air, a slice of lake-silver wafting like a leaf. Then another followed it. Then a few more, then a dozen. Then a hundred, each of them like a butterfly with its wings made of water. Then a whole flock of blue-green and silver-blue wings, their backs shining like the surface of the lake.

They spooled away like they always did, showing me the dark underneath the water.

The person I’d just met stared into the shimmering dark. And it took that for me to realize they’d seen it.

The world under the lake had opened for someone besides me.

Maybe it was the wonder in their face. Maybe it was the raw fear. But I led them into the world under the lake, a place I’d never shown anyone because I’d never been able to show anyone.

They looked around and wondered at the coyotes and sharks with eyes that glowed like embers, and the water star grass growing taller than either of us.

They didn’t stay long. Just long enough to make sure they’d lost whoever was following them.

I didn’t find out their name, or their pronouns for sure, not then. As soon as the world under the lake opened back up to the inlet, they took off, yelling “Thank you” over their shoulder.

Sometimes I do things without thinking, and back then I did that a lot. Talking faster than I was supposed to. Interjecting a random fact about limestone or dragonflies without giving any context. Leaving to do something Mom asked me to do while she was still talking, because I was pretty sure I knew what she wanted from the car, and I was never any good at standing still and listening to directions.

But the other side of that is that sometimes I freeze. When I should do something, I stay still. So many corners of my brain buzz at the same time, a hundred threads of lightning crackling through dry air, that no one thread comes forward. No path or direction makes any more sense than dozens of others, and I do nothing.

So I realized, about a minute too late, that I should have asked where to find them. Or at least called after them to ask their name.

But by the time I thought of that, they were gone.

LORE

I never told anyone what happened, what I saw.

And Merritt never told anyone about that hit I got in. He’d never admit that a girl had gotten him. Not that I was a girl, but that’s how he saw me. That’s how everyone saw me back then.

But Merritt shutting up didn’t stop Jilly and her friends. So he got a good couple of weeks of When’s your next fight? I want to make sure I get a good seat, and You want my little sister to kick your ass next? And he never forgot it.

He pretended he did. But I saw it in his face, years later.

I wish that had been the last time I fought back, the only time, but it wasn’t.

BASTIÁN

My parents have different memories of what made them take me to Dr. Robins. Mom says it was my changes in speed, the pacing around, climbing things, and then staring out windows, not hearing her when she talked to me. Mamá says she started worrying when I was inconsolable over forgetting a stuffed bear at a park, not because I didn’t have the bear anymore, but because I thought the bear would think I didn’t love him.

My brother thinks it was the thing with the cat.

I kept ringing the neighbors’ doorbell every time their cat was sitting outside like she might want to come in, and then started sobbing about whether the cat was okay when Mamá told me you have to stop doing this.

All the restlessness inside me was spilling out, like I was too small to hold it all. If I had to sit still, I bit my nails or pulled at a loose thread on my shirt. Adults kept calling me daydreamy and lost in thought like they always had, but now they also called me fidgety, a nervous kid, or they used euphemisms. And I knew what every one of them meant.

Trouble staying on task referred to me filling in half a coloring page and then deciding I absolutely had to check on the class fish, right then. Difficulty listening meant I might have been listening, but the directions didn’t soak into my brain enough for me to do what I was supposed to. Overly reactive meant that when I accidentally knocked over a jar of paint or broke a pencil, I treated it as a disaster I had caused, like all the other paint jars and pencils might follow suit and just tip over or snap on their own.

Somewhere between that first appointment and when Dr. Robins explained to me what ADHD was, Antonio sat down with me at the kitchen table on a Sunday. “You having a rough time, little brother?” he asked.

I didn’t answer. I kept coloring a drawing, trying not to grip the pencils so hard they’d crack in my hands.

“We’re gonna do something together, okay?” Antonio said. “You and me.”

That was the afternoon he taught me to make alebrijes, to bend wire into frames, to mold papier-mâché, to let them dry and then paint their bodies.

“Our bisabuelo,” Antonio told me as he set out the supplies, ran the water, covered the table, “the family stories say he learned to make alebrijes from Pedro Linares himself, did you know that?”

Everything I knew about alebrijes I knew from Antonio. He crafted whales with magnificent wings. Birds with fins for tails. Snakes that looked like they were trailing ribbons of flame.

“When I don’t know what to do with something,” Antonio said as he adjusted the curve of a wire, “I do this.” He said it as casually as if he were talking to himself.

“If I have a bad day, or a fight with my girlfriend, or I’m frustrated with something at work”—he went on later, the milk of papier-mâché on his fingers—“I just think about it when I’m making alebrijes. For just this little bit, I think about it as much as my brain wants to.”

My inexperienced fingers made lumpy, nondescript monsters that looked like rocks with wings, or lopsided fruit with equally lopsided antlers. Not the perfect animals Antonio made, like the one he was working on now, a lizard with fish fins and a flamelike tongue, so it looked like a dragon.

But I watched him, and I listened. My hands bent the wire, held the cold papier-mâché, glided the paintbrush over.

Everything rushed into my head at once. The neighbors’ cat. The stuffed bear. How hard it was for me not to interrupt people, not because I didn’t care what they were saying, but because I could guess where they were going and was excited about it. How when people got too close to me I wanted to physically shove them away, and it took so much energy not to.

“One thing, okay?” Antonio said.

I looked up at him.

“Just pick one thing that bothers you,” he said, “and give it as much space in your brain as it wants, just for now.”

I shut my eyes. I tried to let one thing float up from the chaos in my brain.

What I thought of, though, wasn’t the cat, or the stuffed bear.

It was Lore. It was how I didn’t even know how to look for them. I’d lost them, so now I’d keep being the only person around here who knew the lakelore was true.

“And then,” Antonio said a while later, when he was painting the lizard that looked like a dragon, “when I’m done, it’s like I can let it go. I got to make it into something, and now it’s something outside of me, and it doesn’t bother me so much, you know?”

I was painting marigold orange onto the back of an alebrije that looked a little like a mule deer. My hands were so restless that my brush left wispy patterns.

But by the time I was done, my hands were a little calmer, my brushstrokes a little more even. The beams of light in my brain, the ones always going in different directions, converged on this one small thing, on this brush, on these colors.

I turned the deer in my hands.

Like Antonio, I had made what bothered me into an alebrije.

It was now something outside of me.

So I kept making them. When something I did wrong got stuck in my brain—when I was frustrated, or impatient, or restless—I made an alebrije.

The yellow marmota with sherbet-orange wings was me losing a take-home test.

The teal cat with the grass-green peacock’s tail was the panic of realizing I’d messed up a course of antibiotics, because I hadn’t learned to keep track of when I ate or when I took pills or even just time itself.

The brown horse with the copper wire tail was my whole body tensing with the effort it took not to kick the guy at school who called me a name I knew the meaning of, but that I also knew I couldn’t repeat to any adult.

A butterfly-spider painted as colorful as a soap bubble reminded me of how painfully slowly I had to learn to transition topics in conversations. I had to learn to say things that connected with what everyone else was saying instead of following my brain as it skipped forward, otherwise I’d get looks of How did you get there? or What does that have to do with anything?

When Dr. Robins asked what I did when I got frustrated or overwhelmed, and I told him about Antonio and the alebrijes, he said, “You have a good brother.” He told me the painting and sculpting I was doing helped with emotional regulation, that it helped interrupt cycles of rumination, terms I was just starting to understand.

There was just one problem.

Within months, the alebrijes crowded every surface in my room. Everywhere I looked, there was a reminder of how many things I worried about, or got fixated on. There was a bat made when Abril frowned and I was convinced she was mad at me and I had done something horrible but couldn’t figure out what. There was a squirrel that held my guilt over yelling I hate this family to my parents because I was hurt about my abuela’s reaction to me changing my name. There was the rounded, porpoiselike body of a vaquita, containing my frustration about the day I mistimed taking my medication, accidentally took it twice, and fell asleep during class.

When I tried to put them away, I felt their agitated buzzing from inside my drawers or under my bed, loud enough that I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t throw them away, not when they were the craft my brother had taught me, this art that went back to our great-grandfather. I couldn’t give them away; that would be giving someone else things I wanted to forget.

I couldn’t ask Antonio what to do either. I imagined him whistling in wonder. Wow, all of those? That’s how often something happens that you need to let go of?

But I had to do something with them. Their sheer numbers were proof of how often I struggled with the ordinary work of existing in the world.

I did figure it out eventually.

It just cost me the world under the lake.

Excerpted from Lakelore, copyright © 2022 by Anna-Marie McLemore.